When the United States passed the 18th Amendment in 1920, banning the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol, few could have imagined just how creative people would become to get around the law. Prohibition was meant to purify society and promote temperance. Instead, it gave rise to a booming underground economy, speakeasies, organized crime, and some surprisingly clever legal workarounds. One of the most fascinating examples? The rise of the “wine brick.”

What Exactly Was a Wine Brick?

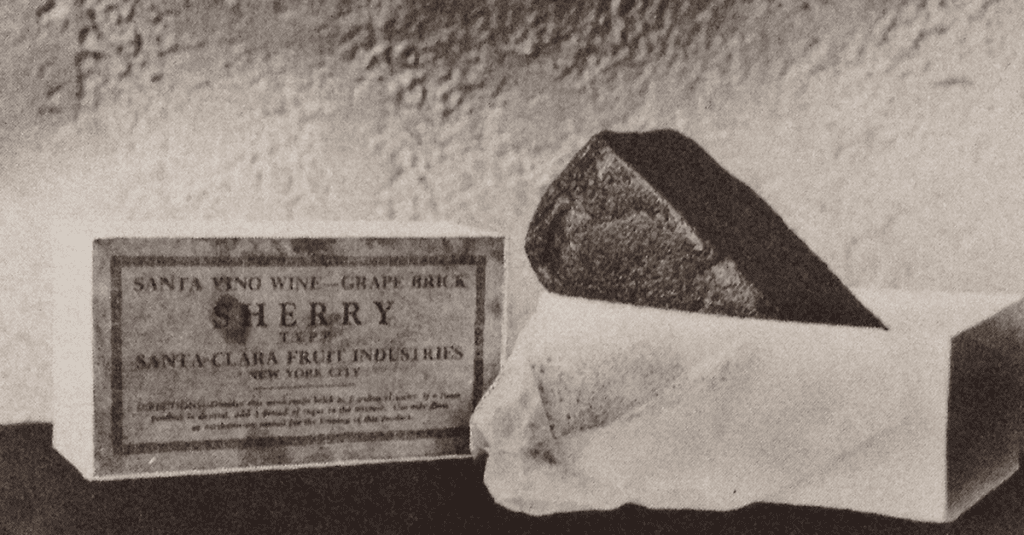

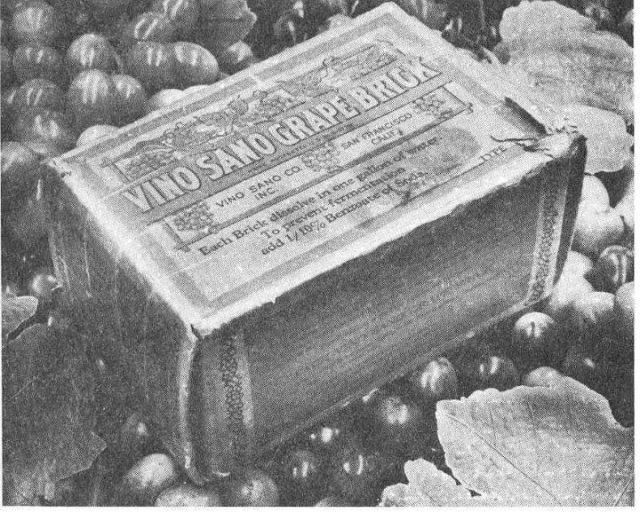

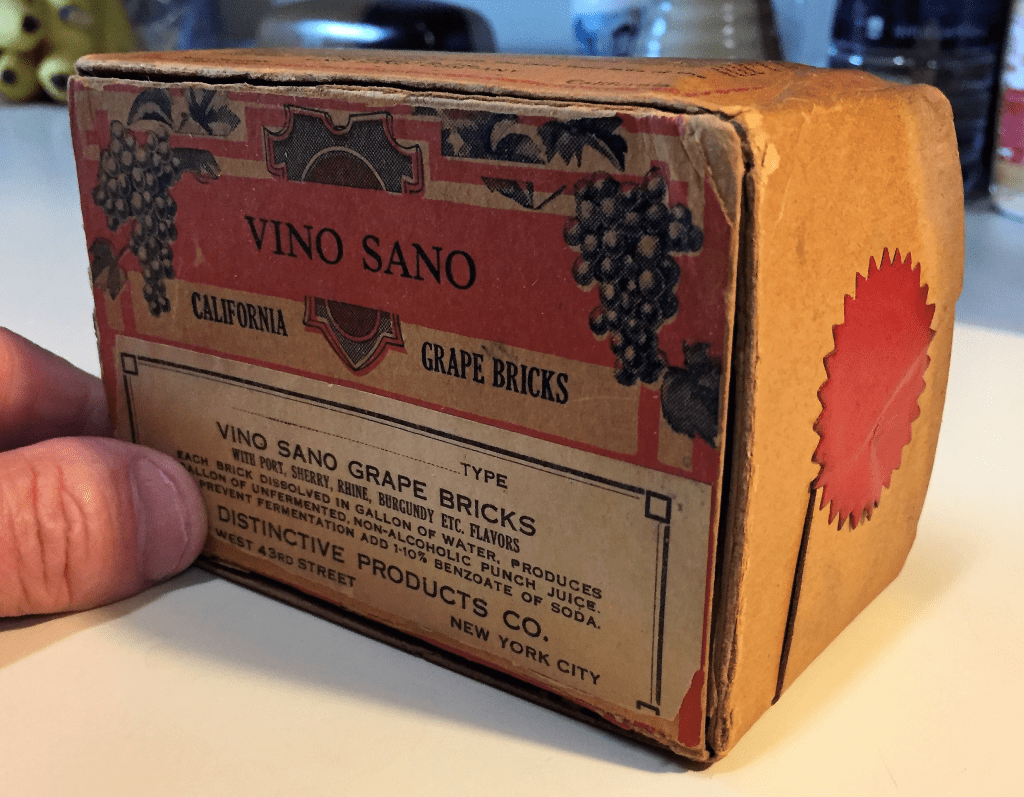

A wine brick was a concentrated block of grape juice extract, usually sold in the form of a dried brick or cube. On the surface, it was completely legal. These bricks were marketed as a convenient way for Americans to make grape juice at home just dissolve the brick in water, and you had yourself a fresh, fruity drink.

But there was a wink behind the product that everyone understood. On the packaging, often in bold letters, was a printed “warning” that carefully told customers exactly what not to do if they wanted to avoid accidentally making wine. The instructions went something like this:

“After dissolving the brick in a gallon of water, do not leave it in a cool, dark place for 21 days, or fermentation may occur.”

Of course, this was no warning at all. It was a carefully disguised recipe for homemade wine—one that millions of Americans followed during the dry years of Prohibition.

Why It Was Legal

The Volstead Act, which defined and enforced the rules of Prohibition, included a key loophole: individuals were allowed to produce up to 200 gallons of “non-intoxicating” fruit juice per year for personal use. This clause was meant to allow families to make grape juice at home but lawmakers underestimated just how quickly that juice could ferment into alcohol under the right conditions.

Video:

A sneaky trick turned grapes into forbidden wine! During Prohibition, grape brick carried sly warn

Winemakers who had once supplied legitimate vineyards quickly shifted their businesses to making grape concentrate bricks. These were sold through catalogs, corner shops, and even mail order. The companies stayed just within the law while knowing full well what customers planned to do with the product.

A Booming Underground Business

Sales of wine bricks exploded in the early 1920s. One company, Fruit Industries Ltd., became especially famous for its bricks made from California grapes. These bricks often came in a variety of flavors such as Zinfandel, Muscatel, and Burgundy none of which made sense if you were only drinking grape juice.

Entire industries grew around this loophole. In Napa Valley and other parts of California, vineyards that had faced ruin after Prohibition suddenly came back to life, converting their production to grape concentrate. By 1925, an estimated 30 million gallons of “grape juice” were being consumed annually most of it had undoubtedly been fermented into wine.

Cultural Impact and Consumer Behavior

Wine bricks were more than just a clever product they represented the American public’s resistance to a law they never fully supported. Many people who had never broken the law in their lives suddenly found themselves becoming home vintners, not out of rebellion, but because they simply didn’t see anything wrong with enjoying a glass of wine at dinner.

Video:

Grape Brick Wine – Prohibition’s Juiciest Loophole

This quiet form of protest also revealed a major flaw in Prohibition policy. It was nearly impossible to legislate morality, especially when the public found ways to comply with the letter of the law while ignoring its spirit.

The End of an Era and a Legacy That Lives On

When Prohibition ended in 1933 with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, the need for wine bricks disappeared almost overnight. But their legacy lived on. The companies that had survived by selling concentrate often returned to making full-bodied wines legally. Some of today’s most famous California wineries managed to stay afloat during the Prohibition years by selling wine bricks.

The ingenuity shown by winemakers and everyday Americans during this time is a testament to human creativity in the face of restrictive laws. Wine bricks are not just a quirky historical footnote they’re a fascinating symbol of resilience, resourcefulness, and a touch of rebellion.

Conclusion

The story of wine bricks is one of the cleverest chapters in American history during Prohibition. They turned a dry law into a booming underground tradition without a single shot being fired. All it took was a brick of grape concentrate, a glass jug, and a “do not ferment” label that said it all.