When people imagine prisoners of war during World War II, they often think of harsh conditions, isolation, and the overwhelming weight of survival. What few realize is that many of these captives refused to let their minds wither behind barbed wire. Instead, they turned their prison camps into makeshift classrooms. Amid the uncertainty of war, these men found purpose in study, preparing themselves for a better life once freedom was restored.

Education in the Unlikeliest of Places

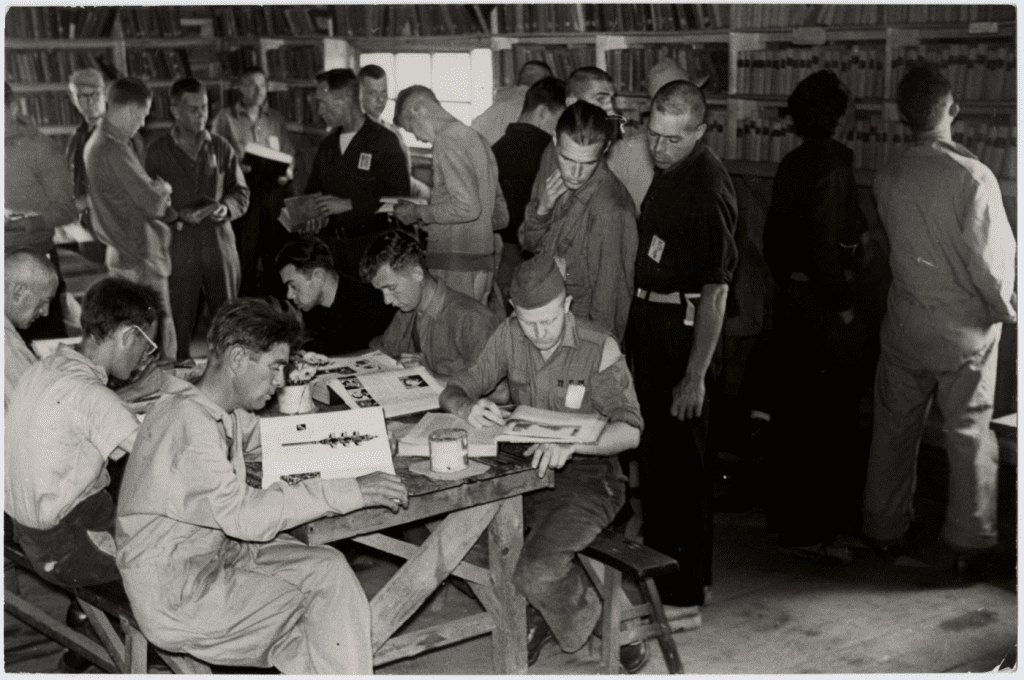

Across Europe and Asia, thousands of Allied soldiers were captured and confined in prisoner-of-war camps. Conditions varied widely, from decent accommodations under the Geneva Convention to brutal and inhumane treatment. Yet even under challenging circumstances, many prisoners sought to reclaim a sense of normalcy and education became one of the most powerful tools in doing so.

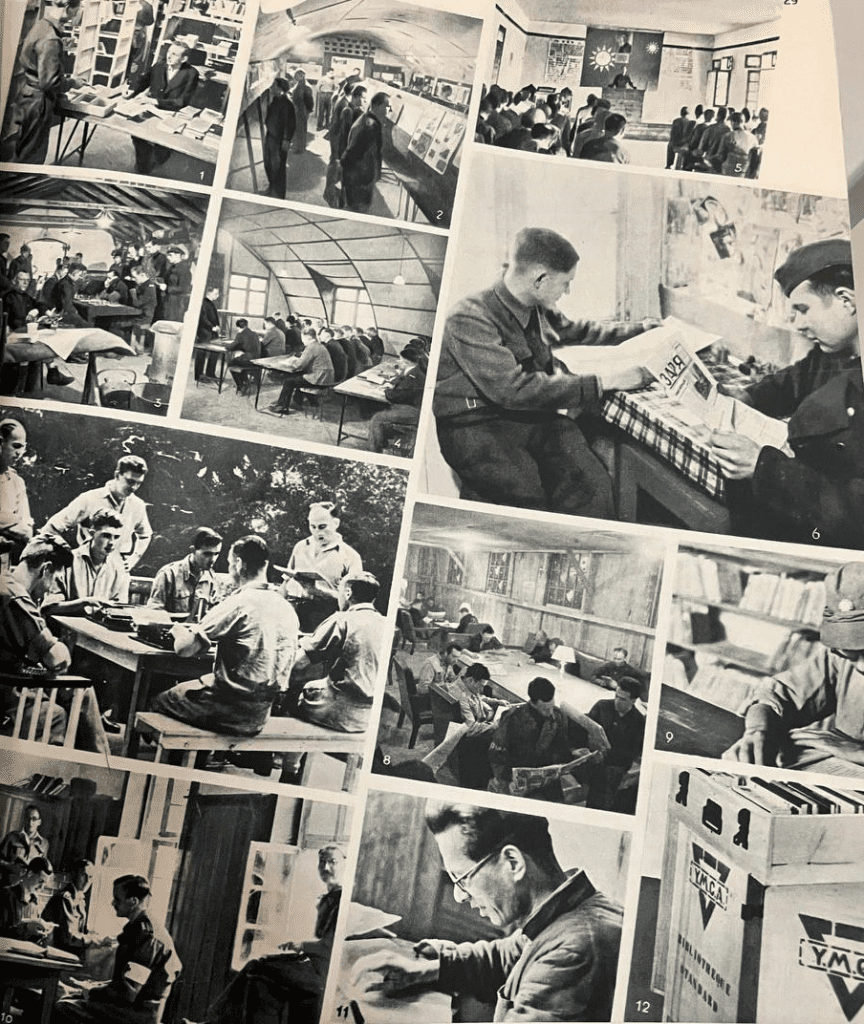

At Stalag Luft III, a German POW camp made famous by “The Great Escape,” Allied airmen set up what became known as the “Kriegsgefangenen Universität” a sort of underground university. Courses included everything from foreign languages and literature to economics and engineering. The goal wasn’t just to pass the time; it was to sharpen the mind and prepare for a life after war.

Video:

Life Behind the Wire: Prisoners of War – Jack Gordon

Learning Without Classrooms

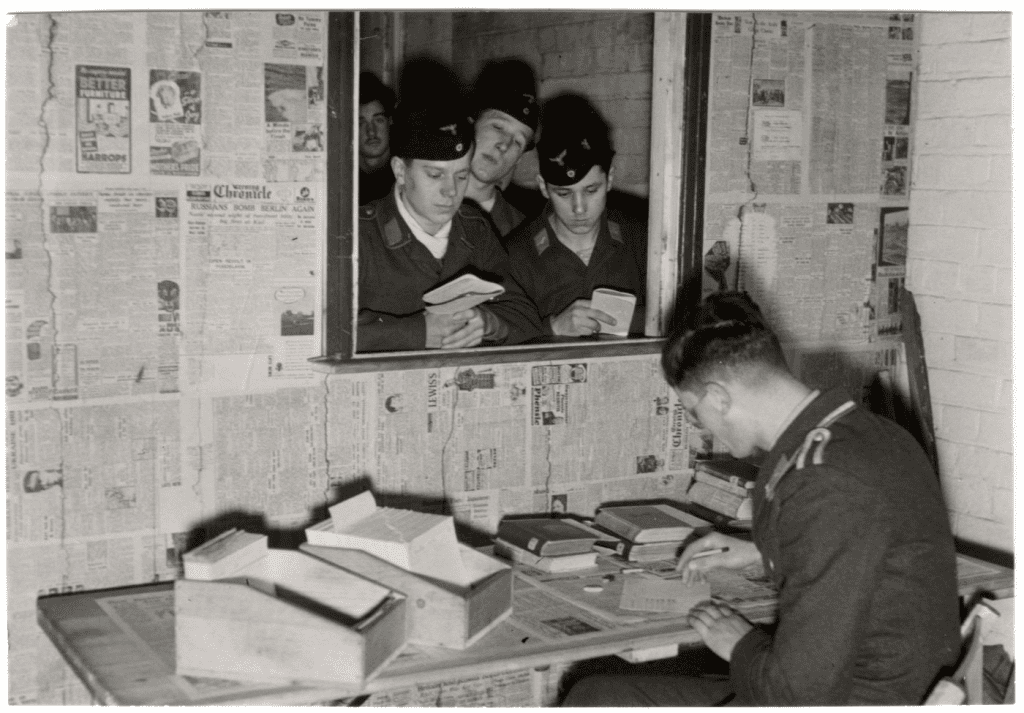

Resources were painfully limited. There were no chalkboards or desks, no official textbooks or lecture halls. But the prisoners adapted. Former teachers, university students, and professionals used their knowledge to lead informal classes. Lessons were often conducted in barracks, and textbooks were sometimes smuggled in through Red Cross packages or recreated from memory.

In British camps, particularly those in Germany, correspondence with the University of London allowed some prisoners to take official exams. These academic efforts were so extensive that after the war, many POWs returned home and received full credit for the studies they completed while imprisoned.

Subjects That Shaped Their Futures

What did they study? The answer is just about everything. German language classes were popular, often taught by fellow prisoners with a talent for linguistics. Engineering courses helped former soldiers pivot into civilian construction and manufacturing jobs. Some took up accounting, law, philosophy, and even art. This wasn’t idle study; it was strategic.

For many, the war had interrupted college or early career training. Continuing their education while captive meant they could resume their ambitions as soon as they returned home. These studies also gave prisoners structure, focus, and hope three things that were in short supply during wartime captivity.

Mental Strength Through Intellectual Growth

Beyond practical skills, this pursuit of knowledge offered psychological refuge. Prisoners who engaged in regular study reported greater morale, resilience, and even improved health. In an environment where daily life could feel meaningless or cruel, education restored a sense of dignity.

Video:

Medicine Behind Barbed Wire: Interned Medical Refugees on the Isle of Man.

This mental focus was especially important for officers, who felt a duty to maintain leadership and discipline among the ranks. Encouraging younger men to study, reflect, and prepare for the future became a way of preserving hope in the face of adversity.

Legacies of Learning in Captivity

After the war, many of these POWs emerged not only physically liberated but intellectually empowered. The education they pursued behind fences and guard towers became the foundation for successful civilian careers. Some went on to become professors, engineers, diplomats, and writers. Others simply used what they had learned to build stronger, more meaningful lives.

One famous example is Lieutenant Airey Neave, who was held in Colditz Castle and escaped to become a key legal figure at the Nuremberg Trials. He later became a member of British Parliament. His time in captivity was not idle it was formative.

Conclusion: Resilience Beyond Resistance

The story of POW education during World War II is a powerful testament to the human spirit. Stripped of freedom, comfort, and security, these men still reached for growth. Their studies were more than an academic exercise; they were acts of resistance, expressions of identity, and blueprints for renewal.

Behind the barbed wire and beneath the weight of war, these prisoners did something remarkable. They refused to let their minds be imprisoned. In doing so, they taught the world that even in the darkest of places, the light of knowledge can still shine.