In 1438, the mighty Inca Empire began to rise high in the Andes under the leadership of Pachacuti. His empire would grow rapidly, stretch thousands of miles, and develop remarkable feats of engineering and agriculture. Yet while the Inca were carving roads through the mountains and building cities in the sky like Machu Picchu, another empire of a different kind had already been thriving for centuries an empire of the mind, rooted in the quiet stone walls of Oxford, England.

By the time Pachacuti assumed power and began expanding the Inca Empire, the University of Oxford had already been a flourishing center of learning for over 300 years. Founded in the 12th century, Oxford wasn’t built on gold or conquest. It was built on the pursuit of truth, study, and the written word. While the Inca organized their empire through oral tradition and quipus (knotted cords used to record information), Oxford scholars were already writing and copying texts, debating theology, mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy.

Two Empires, Two Visions of Power

The rise of the Inca Empire was fast and formidable. It became the largest empire in pre-Columbian America, stretching across present-day Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, and beyond. It thrived on innovation, developing terraced farming systems, an extensive road network, and sophisticated architecture without the use of the wheel or written language.

In contrast, Oxford grew not through territorial expansion but through intellectual depth. It became a gathering place for some of the greatest minds in European history. Long before the printing press arrived, Oxford scholars were preserving ancient manuscripts by hand, translating Arabic texts into Latin, and debating Aristotle in candlelit halls.

One empire ruled with absolute authority and vanished within a century of its height. The other, while slower and quieter in its influence, has endured for nearly a millennium.

Video:

The Inca Empire Explained in 11 Minutes

The Fall of the Inca and the Resilience of Oxford

The Inca Empire collapsed less than a hundred years after it rose. Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro arrived in the early 1500s and brought devastating disease, warfare, and colonization. Though many Inca achievements survived in legend and stone, the empire itself faded into history.

Meanwhile, Oxford remained steadfast. Despite wars, plagues, political upheaval, and massive societal changes, the university continued to grow. Its resilience is rooted in a singular mission: to learn and to teach. From medieval theologians to modern Nobel Prize winners, Oxford has continually adapted to the times without losing its core purpose.

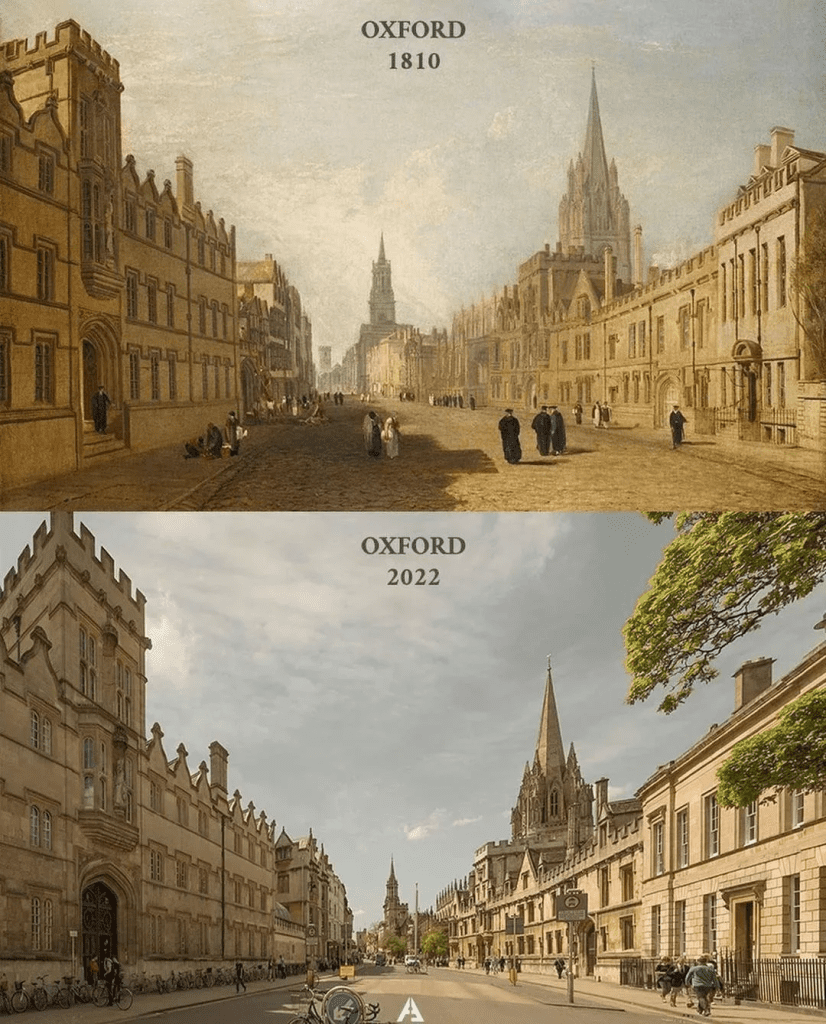

Oxford Today: A Living Testament to Knowledge

Now more than 900 years old, Oxford is the oldest university in the English-speaking world. Its libraries hold millions of books, and its colleges brim with students from every corner of the globe. The same halls that once echoed with Latin prayers now ring with the languages of the world, as new generations take up the eternal challenge of understanding, discovery, and wisdom.

Video:

Early History of the University of Oxford

Unlike empires of stone and sword, Oxford was never meant to conquer. It was built to endure and it has. Its survival through centuries is not just a historical curiosity. It’s proof that ideas, once nurtured and passed on, can outlive kingdoms and reshape civilizations.

Conclusion: Knowledge Over Time

The story of Oxford and the Inca is not about which was greater it’s about what lasts. The Inca built wonders that still awe us today, and their cultural legacy remains vital to indigenous communities in South America. But Oxford’s legacy is measured in centuries of uninterrupted learning. In an age when so much is temporary, it stands as a living symbol of how education carefully nurtured, continuously pursued can be the most enduring force in human history.

As we look at the ruins of Machu Picchu and the lively courtyards of Oxford, we are reminded that while empires may rise and fall, the thirst for knowledge remains eternal.