In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a quiet revolution unfolded inside the walls of the Harvard College Observatory. It didn’t involve powerful telescopes, rockets, or even stargazing under open skies. Instead, it was led by women barred from using the very telescopes they were helping to calibrate who transformed our understanding of the cosmos with nothing more than glass photographic plates, mathematical precision, and unshakable perseverance.

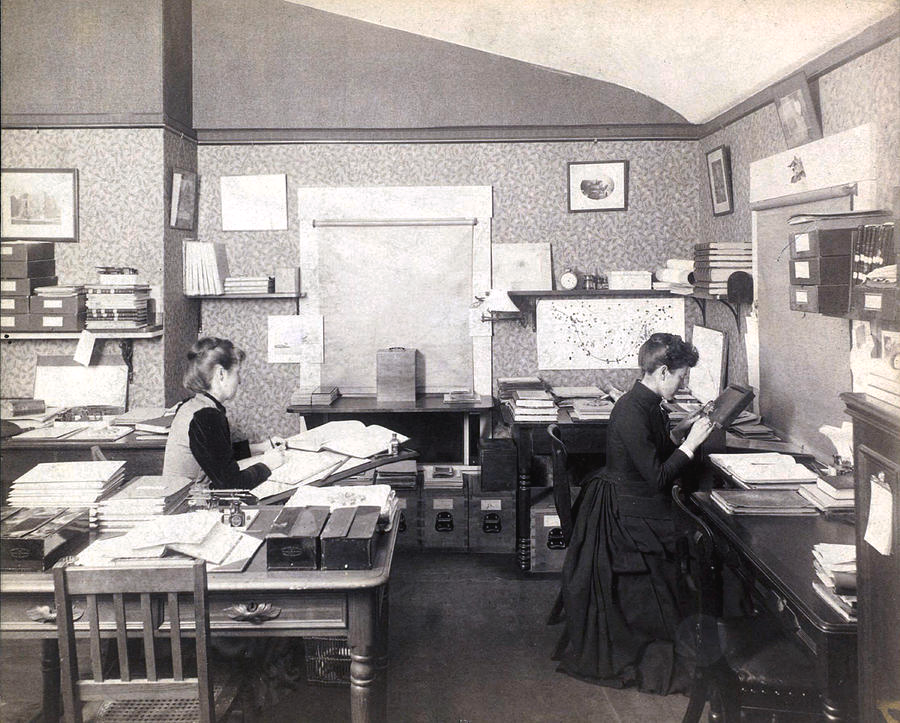

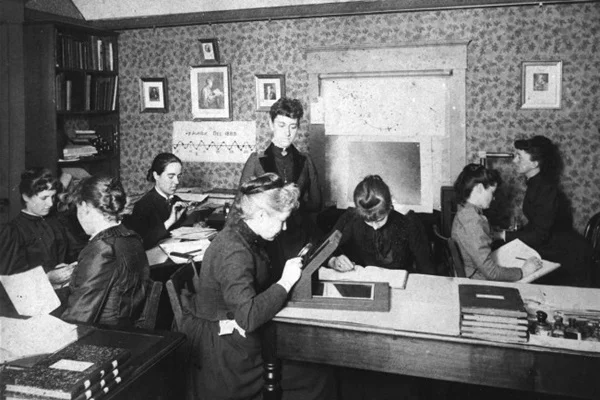

These women, later known as the Harvard Computers, were initially hired to perform what was considered tedious clerical work: examining glass plates of the night sky and cataloging the stars they saw. But their work was anything but mundane. Over time, they became pioneers in astronomy, responsible for discoveries that still shape the field today.

Studying the Stars Without a Telescope

At a time when women were excluded from most scientific institutions, these astronomers-in-disguise worked behind the scenes at Harvard, studying black-and-white plates covered in tiny dots each representing a distant star. Without access to telescopes or field research, their contributions might have remained invisible. But they found a way to see what others could not.

Using these photographic plates, the Harvard Computers manually recorded the brightness and position of stars, detecting patterns, changes, and variables that male astronomers often missed. One by one, they mapped the sky, logging thousands of data points that built a foundation for future discoveries.

Video:

The Harvard Computers – Origins of the Stellar Classification System

Henrietta Swan Leavitt: Unlocking the Universe’s Scale

Among these extraordinary women, Henrietta Swan Leavitt made a discovery that changed astronomy forever. While analyzing Cepheid variable stars stars that regularly brighten and dim she observed a pattern: the brighter the star, the longer its pulsation period.

This relationship, known today as the Leavitt Law, became the key to measuring distances in space. Thanks to Leavitt’s work, astronomers could now determine how far away stars and galaxies were effectively giving science a way to measure the scale of the universe. Her findings were instrumental in helping Edwin Hubble later discover that the universe is expanding.

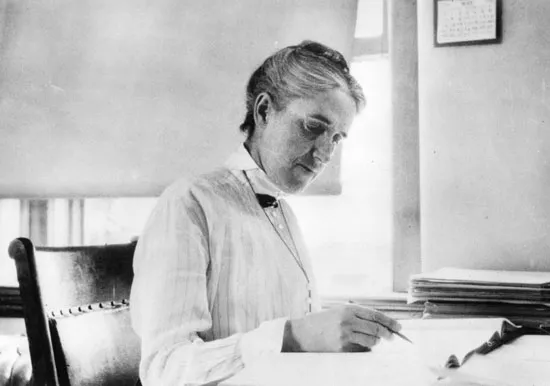

Annie Jump Cannon: Bringing Order to the Stars

If Leavitt helped us measure space, Annie Jump Cannon helped us understand what it’s made of. An expert in classifying stellar spectra, Cannon sorted hundreds of thousands of stars based on their light patterns. She refined the Harvard Spectral Classification system into the simple, elegant O, B, A, F, G, K, M sequence we still use today.

Cannon’s work brought clarity to the chaotic observations of stellar light. With her classification system, astronomers could better understand the temperature, composition, and life stages of stars essential knowledge in the study of stellar evolution.

Invisible Labor, Lasting Impact

Despite their enormous contributions, the women of the Harvard Observatory were often overlooked in scientific circles. They were rarely credited on papers, paid significantly less than their male counterparts, and were labeled as “computers” rather than scientists.

Video:

10 Famous Women in Astrophysics

Yet they persisted. Their meticulous work laid the groundwork for discoveries that would reshape humanity’s understanding of its place in the universe. And they did it all while quietly challenging the gender norms of their time.

A Legacy Written in the Stars

Today, we remember these women not as assistants, but as astronomers in their own right. Their work has earned renewed attention through books, documentaries, and exhibits, finally giving them the credit they long deserved.

They never aimed for fame or spotlight. They simply followed the stars through lenses, math, and unwavering determination. In doing so, they helped us see farther, think bigger, and recognize that brilliance often shines brightest in the places we least expect.

The Harvard Computers didn’t just map the night sky. They redrew our place in the cosmos.