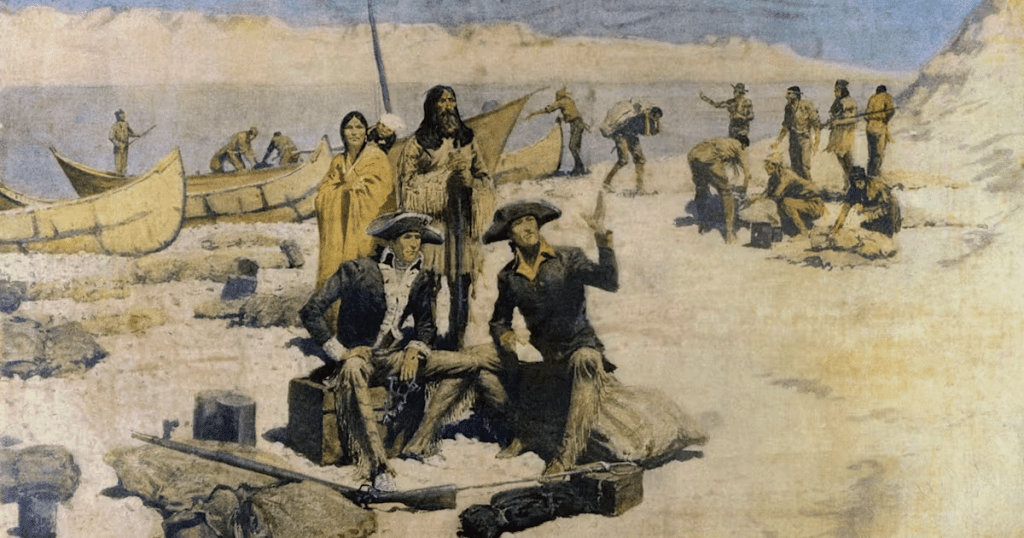

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set off on their epic journey across the uncharted American West in 1804, they could never have imagined that tiny traces of their illnesses specifically the treatment of them would still be telling their story over two centuries later.

Thanks to modern science, researchers have been able to pinpoint more than 600 of the famed expedition’s campsites not through journal entries or vague maps, but by detecting microscopic clues left behind in the most unlikely of places: latrines.

An Unexpected Legacy: Mercury in the Soil

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, carried an extensive medical kit on their 8,000-mile journey, including a popular 19th-century remedy called “Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pills.” These massive tablets, often nicknamed “thunderclappers,” were commonly used to purge the system and treat a host of ailments, from constipation to general malaise.

The key ingredient? Mercury.

At the time, mercury was thought to be a legitimate treatment for many conditions. Its powerful laxative effect made it a go-to for frontier medicine. What the explorers didn’t know, however, is that mercury is a toxic metal that doesn’t degrade easily. Instead, it can remain in soil for centuries especially in areas like latrines where bodily waste was deposited regularly.

Video:

The Lewis & Clark Expedition: The Most Dangerous in American History

From Trailblazing to Tracking: How Science Follows the Path

Fast forward to the 21st century, and researchers are using this overlooked aspect of the expedition to retrace the journey with startling precision. By collecting soil samples in areas thought to have hosted Lewis and Clark’s campsites, scientists have found elevated levels of mercury traces from those very same “thunderclapper” pills.

Each mercury-rich latrine offers a GPS-like marker that confirms a campsite’s location. With this method, researchers have been able to verify and map more than 600 sites along the expedition’s route, offering historians and archaeologists invaluable data about where the group camped, how long they stayed, and even aspects of their daily routines.

Why It Matters: A New View of American History

This discovery has revolutionized how we understand the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Previously, much of what we knew came from their journals, sketches, and the maps they painstakingly created. While those records are invaluable, they were still subject to error, bias, or the limitations of 19th-century navigation.

But now, science fills in the blanks.

By identifying latrines and other high-mercury areas, we’re able to uncover smaller, forgotten sites that never made it into the journals. These findings give a more complete picture of the expedition not just the major milestones, but the everyday moments that defined this pivotal journey through American wilderness.

A Dose of Irony: The Pill That Keeps on Giving

It’s a curious twist of fate that a toxic medicine, meant to treat illness, has ended up being the key to unlocking one of the greatest exploratory journeys in American history. The mercury that once flowed through the veins of Lewis, Clark, and their fellow explorers is now a breadcrumb trail for curious scientists and history buffs alike.

Video:

10 Cool Facts About The Lewis & Clark Expedition

And while we now know the dangers of mercury, there’s no denying the value it has offered modern-day historians. Without it, many of the expedition’s stops would have been lost to time swallowed by the land they once struggled to cross.

Final Thoughts: History Hiding in the Dirt

Sometimes, history doesn’t survive in the pages of a journal or in a well-preserved artifact. Sometimes, it lingers quietly underground, waiting to be unearthed by a curious mind and a scientific tool. The mercury-laced trail left by Lewis and Clark is a perfect example of how even the most mundane human activities like using the bathroom can become valuable clues for future generations.

Thanks to their “thunderclapper” pills, the Corps of Discovery unknowingly documented their presence with each step they took westward. And in doing so, they left behind not just stories but science.