In the mid-19th century, two brilliant minds stood against a tide of ignorance and medical tradition. Ignaz Semmelweis and Florence Nightingale, both pioneers in their own right, recognized something shockingly simple: handwashing saves lives. Yet despite their clear evidence and tireless efforts, their warnings were dismissed, even ridiculed, for decades.

Today, their legacy lives on especially in times of global health crises when proper hygiene is vital. But few know the full story of how these two figures were silenced, and how long it took the world to finally listen.

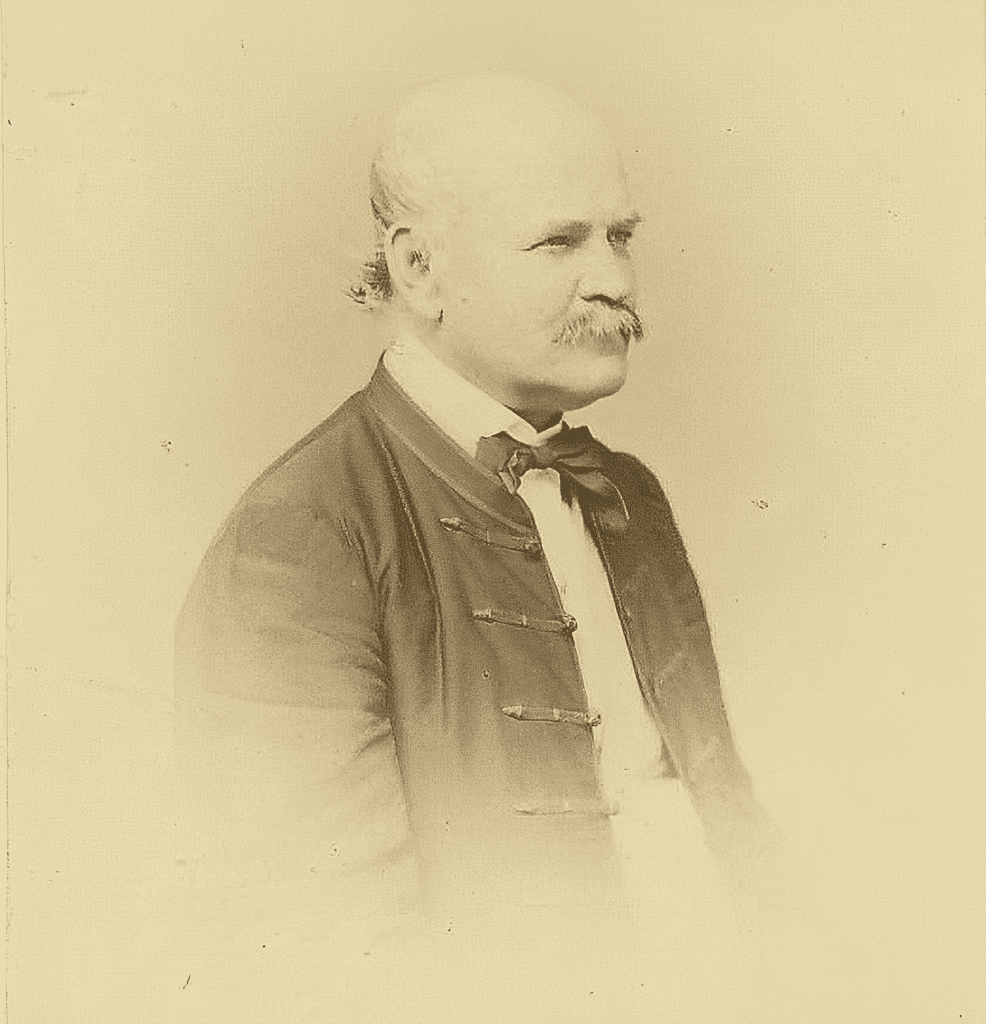

Semmelweis and the Tragedy of Truth

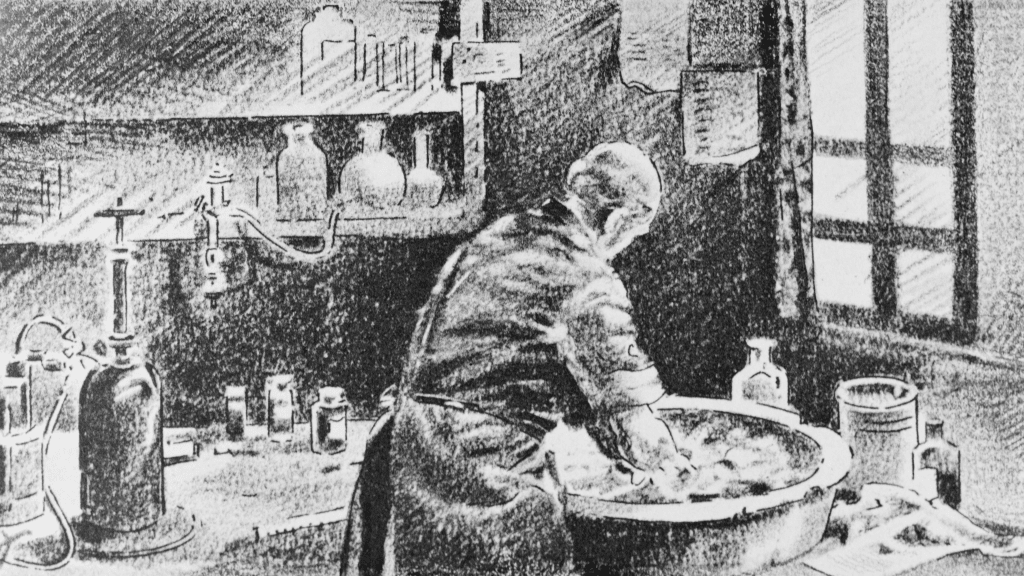

Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician working in Vienna in the 1840s, made a groundbreaking observation. While overseeing maternity wards, he noticed that women treated by doctors had significantly higher death rates from puerperal fever (childbed fever) than those cared for by midwives. After methodically analyzing every variable, he concluded that the doctors who frequently went straight from autopsies to delivering babies were transmitting deadly infections.

His solution? Wash hands with a chlorine solution.

It worked. Death rates in his clinic dropped dramatically. You would think such a life-saving discovery would be celebrated. But it wasn’t. Semmelweis was mocked, attacked, and eventually pushed out of his position. He died in an asylum in 1865, his findings largely buried under professional egos and medical orthodoxy.

Video:

Ignaz Semmelweis – The Persecuted Medical Pioneer

Nightingale’s Quiet Revolution

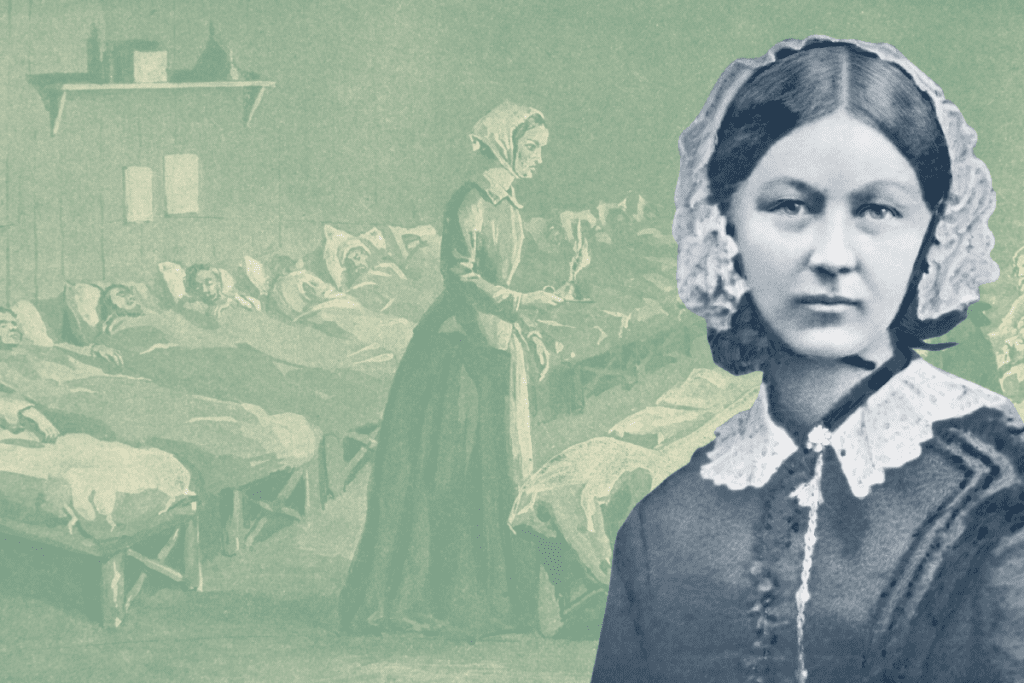

While Semmelweis was being ignored, Florence Nightingale was transforming military hospitals during the Crimean War. Known as “The Lady with the Lamp,” she believed that cleanliness including regular handwashing was essential to healing. Her reforms cut death rates in British military hospitals from 42% to just 2%.

Unlike Semmelweis, Nightingale had powerful connections and the social standing to push for change. But even she faced resistance. The germ theory of disease was still emerging, and many doctors clung to outdated practices.

Still, Nightingale persisted. She revolutionized nursing and public health, using statistics and sanitation as her weapons. Her influence laid the foundation for modern hospital hygiene. Yet, despite her successes, even her advocacy didn’t immediately cement handwashing as a medical standard.

A Century of Stubbornness

What’s baffling is how long it took the medical community to accept something so obviously effective. Even as evidence piled up through the work of Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, and others many doctors resisted change. Pride, tradition, and disbelief in microscopic organisms all contributed to a century-long delay in adopting basic hygiene practices.

Video:

Florence Nightingale: Changing the Field of Nursing – Fast Facts | History

It wasn’t until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that handwashing began to be accepted as a critical part of medical care. And it wasn’t until the late 20th century that public health organizations truly emphasized it for everyone, not just surgeons and nurses.

The Lesson We Still Need to Learn

Fast forward to today, and hand hygiene is finally recognized for what it is: one of the simplest, most effective tools in preventing the spread of infections. From flu outbreaks to global pandemics, the importance of washing hands has never been more widely understood or more desperately needed.

Yet the story of Semmelweis and Nightingale serves as a sobering reminder. Even the clearest truths can be ignored when they challenge the status quo. And even the simplest acts like washing our hands can be the difference between life and death.

Conclusion: Honoring Their Legacy

Semmelweis died in obscurity, and Nightingale was underappreciated in her time. But their insights laid the groundwork for modern medicine’s most fundamental practice. We owe them more than historical footnotes we owe them our health.

Next time you wash your hands, remember: it’s not just about staying clean. It’s about standing on the shoulders of giants who tried to warn the world and were nearly forgotten for it.