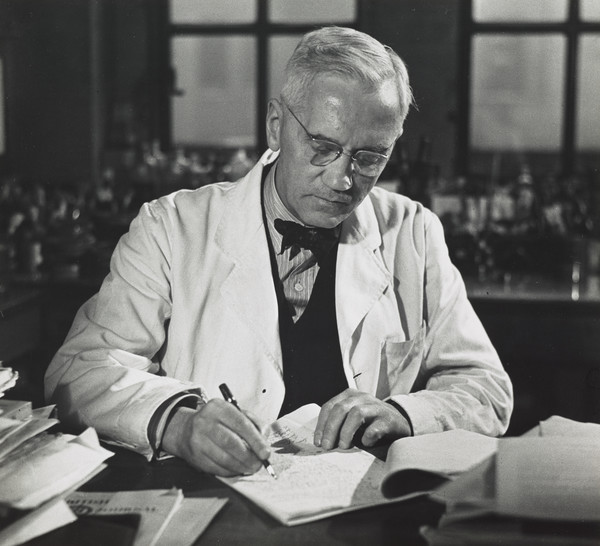

In the quiet of his London laboratory in 1928, Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming made an accidental discovery that would revolutionize medicine. What he found wasn’t flashy or dramatic at first glance a forgotten Petri dish with bacteria, strangely surrounded by a clear ring where mold had taken over. But that simple observation led to the birth of penicillin, the world’s first true antibiotic, and forever changed the fight against infection.

A Fortunate Accident

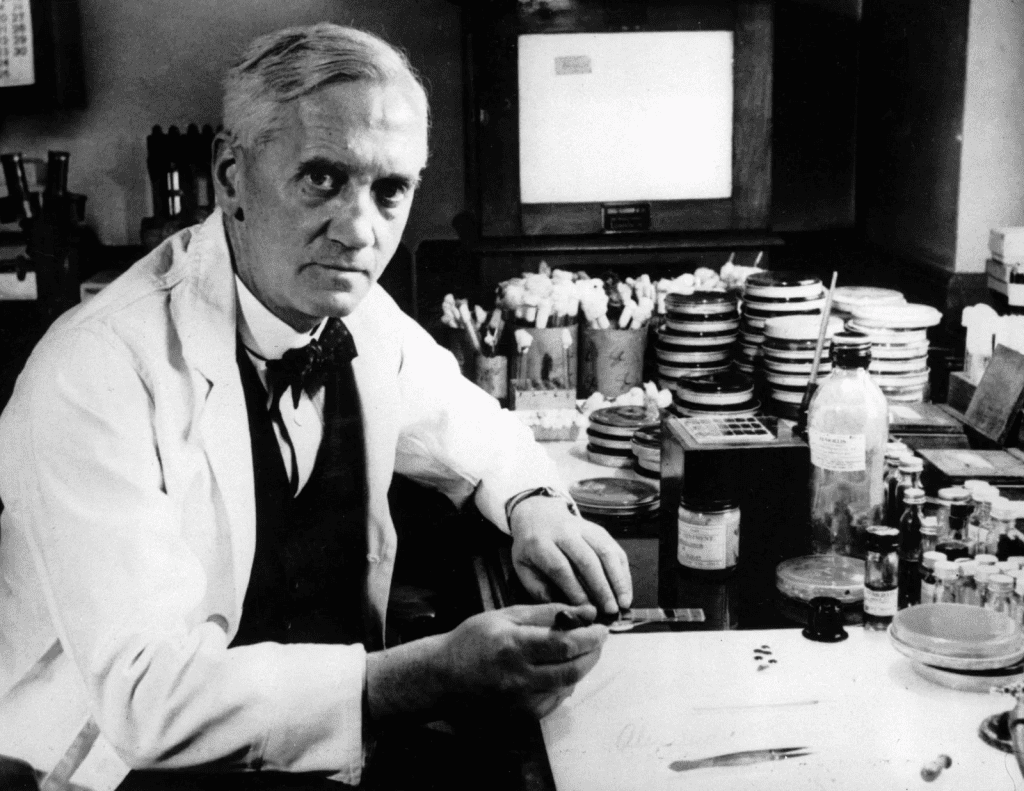

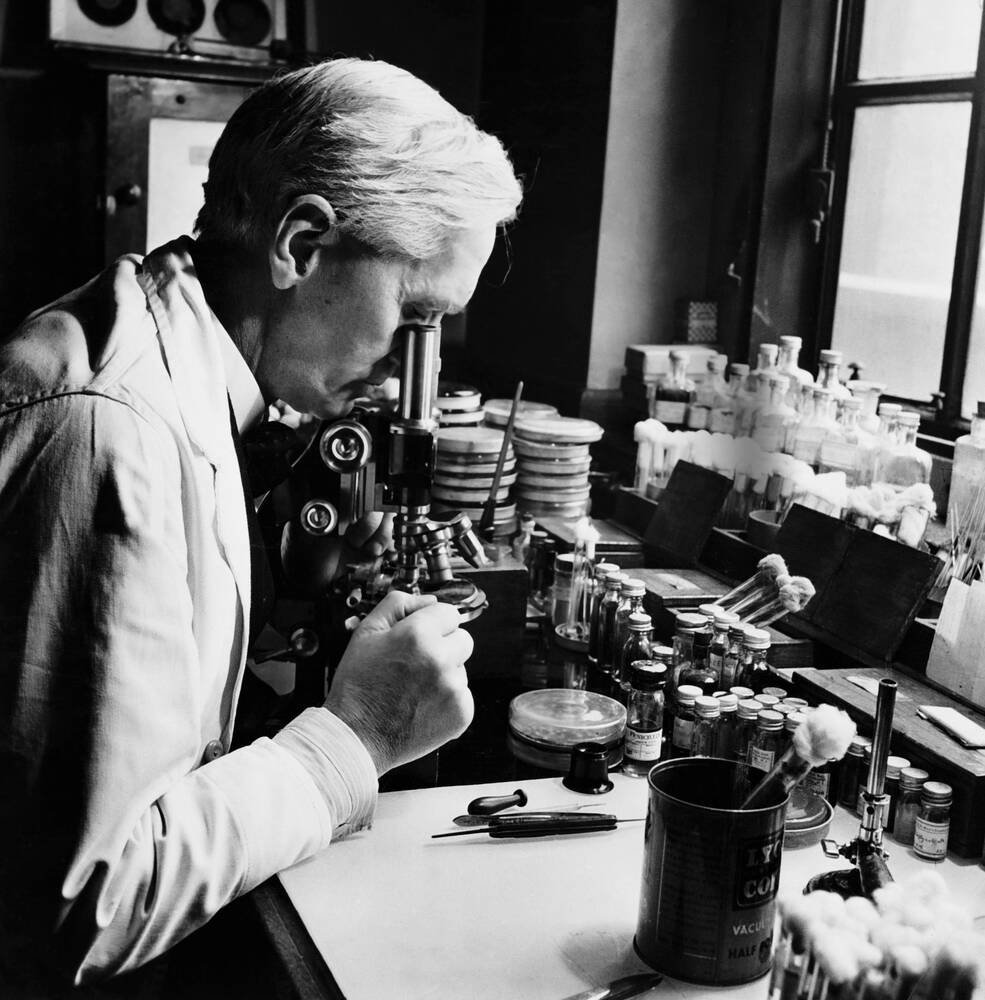

Fleming had been working with staphylococcal bacteria at St. Mary’s Hospital when he returned from vacation to find something odd. One of the dishes had been contaminated with mold something that would usually ruin an experiment. But instead of tossing it aside, Fleming noticed something curious: the bacteria around the mold had been destroyed, while those farther away remained untouched.

This mold, identified as Penicillium notatum, had released a substance capable of killing harmful bacteria. Fleming named the substance “penicillin.” At the time, he could hardly have imagined just how world-changing his discovery would become.

A Discovery Ahead of Its Time

Though Fleming published his findings in 1929, the world wasn’t ready yet. The scientific community acknowledged his work, but turning penicillin into a reliable treatment required more than recognition—it needed technology, funding, and innovative minds.

Video:

The accident that changed the world – Allison Ramsey and Mary Staicu

That’s where two other scientists came in: Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain. A decade later, at the University of Oxford, they picked up where Fleming had left off. Their team figured out how to purify penicillin and test its effectiveness on mice, then on humans. The results were astonishing. Infections that once killed quickly could now be reversed within days.

Penicillin Goes to War

World War II accelerated the demand for antibiotics. With soldiers dying from infected wounds as much as from bullets, the race was on to mass-produce penicillin. American pharmaceutical companies, backed by the government, began large-scale production using deep-tank fermentation.

By 1945, penicillin was widely available, saving thousands of Allied lives. That same year, Fleming, Florey, and Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their life-saving work.

Millions Saved and a Cautionary Note

Penicillin opened the floodgates to a new era of medicine. Soon, more antibiotics followed, each one offering a powerful weapon against diseases that had once seemed unstoppable: pneumonia, syphilis, scarlet fever, and more.

Video:

Alexander Fleming Biography

But even then, Fleming was aware of the potential danger. In his Nobel acceptance speech, he warned that misuse of antibiotics could lead to resistance. If people used penicillin too casually or failed to complete prescribed treatments, bacteria could evolve and render the drug ineffective.

His words were prophetic. Today, antibiotic resistance is a global health threat. Bacteria like MRSA and drug-resistant tuberculosis remind us that even miracle drugs have limits.

A Legacy That Continues

Alexander Fleming didn’t set out to change the world he stumbled onto penicillin by paying attention to something most would have discarded. But his curiosity and persistence, paired with the brilliance of Florey and Chain, ushered in a medical revolution.

Thanks to them, millions of lives have been saved. And while we face new challenges in the antibiotic era, the lesson remains: science often advances not with fanfare, but with a keen eye, an open mind, and the willingness to follow where the evidence leads.