When we think of early steel-making, most of us imagine industrial furnaces in 19th-century Europe or innovations in Asia. But centuries before that, in the heart of East Africa, the Haya people of ancient Tanzania had already developed a sophisticated steel-forging technology that astonished modern scientists. Using animal-skin bellows and a process involving preheated air, the Haya were producing high-grade steel long before similar advancements appeared in Europe.

This remarkable feat of ancient African metallurgy not only reshapes how we view early technological history, but it also challenges persistent myths that underplay the scientific achievements of African civilizations.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

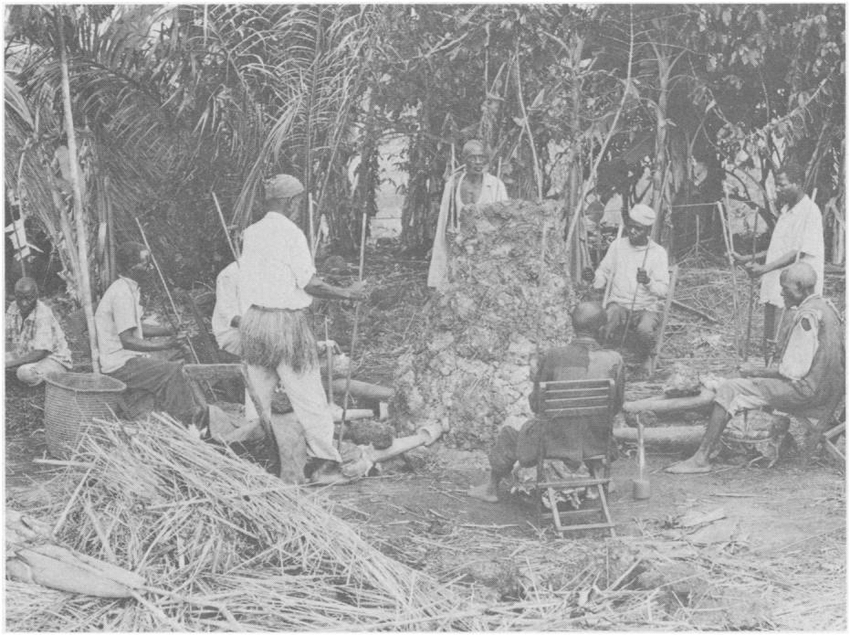

In the 1970s, British anthropologist and archaeologist Peter Schmidt and metallurgist Donald Avery were conducting research in northwestern Tanzania when they came across something astonishing. Oral histories from local Haya elders described ancient iron furnaces used by their ancestors furnaces that had not been used in generations but remained embedded in cultural memory.

Curious and skeptical, Schmidt and his team asked the elders to reconstruct one of these traditional furnaces using the old methods. What followed stunned the academic world.

The furnace, made from clay and fired using animal-skin bellows, reached temperatures as high as 1,800°C (3,300°F). That’s hotter than many early European blast furnaces. Even more impressive? The Haya used preheated air injection, a technique thought to have been developed in Europe only in the 1800s. The steel produced was high in carbon, incredibly strong, and suitable for tools and weapons.

This was centuries before the European industrial revolution and it had been happening in East Africa all along.

Video:

The Haya People: Ancient Iron Smelters Of Africa

The Science Behind the Haya Steel Process

What made the Haya’s process so advanced wasn’t just the heat it was their understanding of airflow and thermodynamics, even if not in the formal scientific terms we use today. By using bellows and piping to preheat the air before injecting it into the furnace, they could maintain higher combustion temperatures more efficiently.

This method allowed the smelters to reach the exact conditions needed to create carbon-rich steel, a material much stronger and more durable than simple iron. And they were doing this not with industrial machinery, but with locally sourced materials, ancient knowledge, and generations of oral engineering passed down through time.

Rethinking Africa’s Role in Global Innovation

For too long, historical narratives have marginalized African contributions to science and technology. Often portrayed as recipients of outside innovation, African societies like the Haya are now being rightly recognized as creators and innovators in their own right.

The Haya’s metallurgical expertise predates Europe’s steel production by over a thousand years. This isn’t just a fascinating archaeological fact it’s a clear indication that technological genius knows no geographic boundary.

Video:

Tree of Iron – PREVIEW

Acknowledging achievements like this forces us to rewrite global history to reflect a more accurate and inclusive understanding of human innovation.

Why This Matters Today

Learning about the Haya’s steel-making mastery isn’t just a matter of historical curiosity. It’s a powerful reminder that knowledge can thrive anywhere, especially when nurtured by tradition, environment, and community collaboration.

In the context of African history, stories like this one push back against long-standing stereotypes that suggest technological stagnation or dependency. In reality, African cultures have contributed to the global body of science and technology for centuries, often in ways the Western world has only recently begun to appreciate.

Cultural Knowledge and Scientific Value

What’s also remarkable about the Haya tradition is how much of it was preserved not in written records, but in oral storytelling and hands-on craftsmanship. When researchers allowed local elders to guide them, they unlocked a scientific heritage that had lived quietly beneath the surface for generations.

It shows us that science isn’t always found in textbooks or laboratories. Sometimes, it’s passed from hands to hands, hidden in rural communities, spoken around fire circles, and embedded in rituals and daily practice.

Conclusion: Recognizing Africa’s Technological Brilliance

The Haya people’s steel production is more than a historical footnote it’s a testament to the ingenuity and innovation of ancient African civilizations. Long before European industrialization, they mastered complex metallurgical processes that stood the test of time.

By celebrating this story, we not only honor the legacy of the Haya but also correct a broader historical imbalance. Africa has always been a land of innovation, and its people have always shaped the world in ways we are only beginning to rediscover.

Next time you hold a steel tool or marvel at engineering, remember that deep in the Tanzanian landscape, a quiet people were already forging the future with fire, air, and wisdom far ahead of their time.