In the aftermath of slavery, amid shattered families and broken records, thousands of formerly enslaved people took up a quiet but powerful fight to find the loved ones they had been torn away from. With little more than faith and hope, they turned to newspapers and a few lines of type to do what even the end of the Civil War couldn’t guarantee: reunite with family.

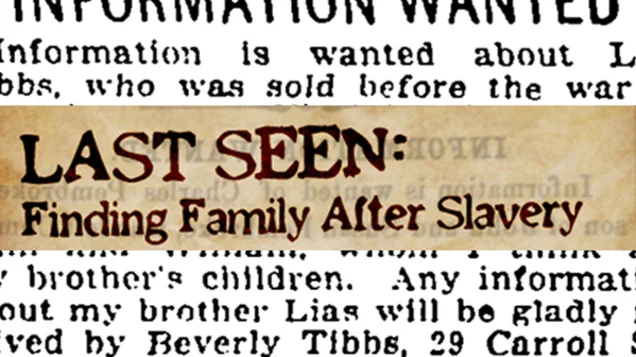

These lines were called “Information Wanted” ads, and they stand today as one of the most moving, overlooked forms of resistance in American history.

A Search for More Than Names

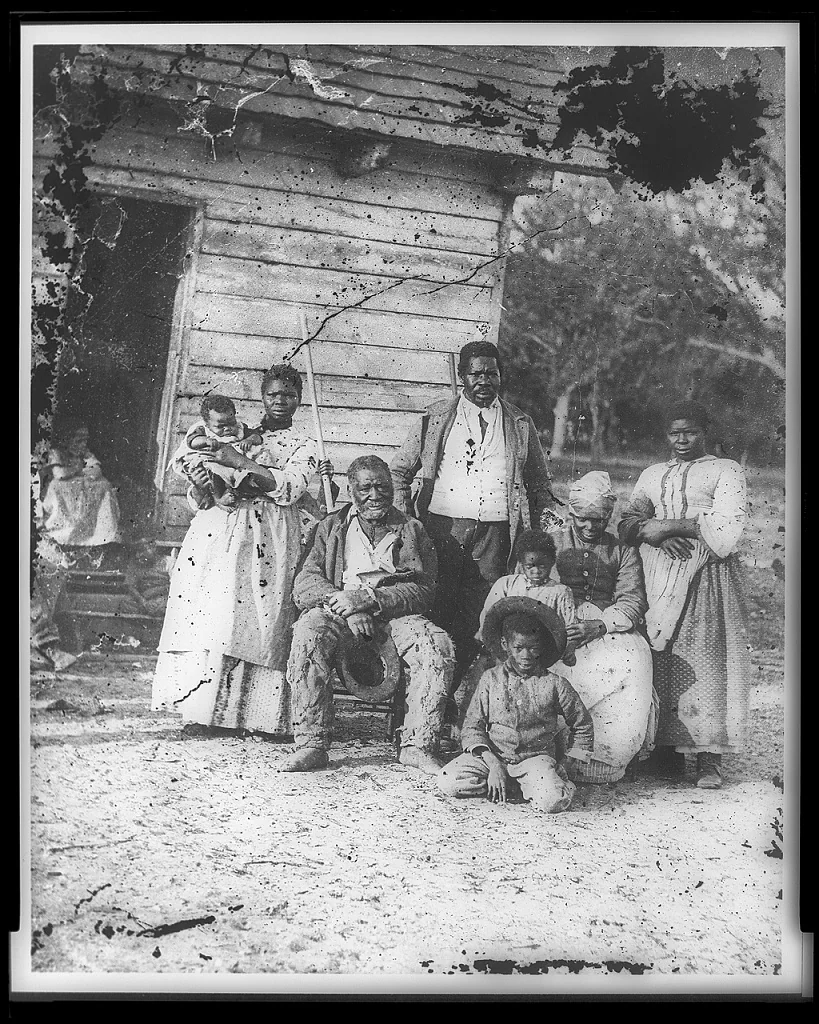

After Emancipation, newly freed Black Americans were finally allowed to travel, own land, and speak freely. But freedom didn’t return what had been lost. Families had been torn apart by sales, forced separations, and systemic brutality for generations. Spouses were sold without warning. Children were taken as property. Siblings were split up with no way to reconnect.

But even after all the pain and silence, many never stopped searching. They turned to a new tool: the press.

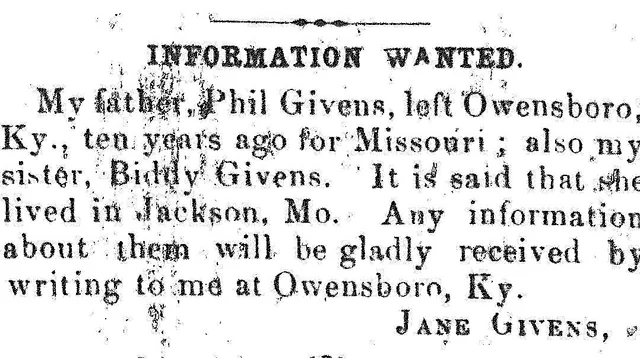

From the 1860s through the early 1900s, thousands of ads began appearing in Black-owned newspapers like The Christian Recorder, The Southwestern Christian Advocate, and others. These ads were heartbreakingly simple, often starting with a phrase like:

“Information wanted of my son, Si Johnson, who was sold in Mississippi in 1857.”

Each one represented a deep, human longing a love that refused to disappear, even when history tried to erase it.

Video: “Information Wanted” Newspaper Ads

Si Johnson and Stories Like His

Si Johnson was just one of many names that appeared in these ads. His mother may not have known if he was still alive, or even what name he might be using now. But she had hope. She placed the ad anyway, hoping that someone reading might remember him, or better yet, be him.

These ads often included every detail the writer could recall slaveholder names, last known locations, physical descriptions, or names of plantations. It was detective work done by those with no maps, no phones, and no institutional support. It was love acting as both compass and lantern.

Some were written by fathers looking for daughters. Others were placed by brothers searching for sisters. Entire communities rallied around these ads, clipping them, posting them in churches, and even reading them aloud in gatherings.

Why the Ads Mattered So Deeply

While most of these ads didn’t lead to reunions, they offered something even deeper: dignity. For centuries, enslaved people had been denied the right to form legal families. They weren’t seen as husbands, wives, or parents under the law only as property. These ads shattered that lie.

By publicly proclaiming their love and longing, these survivors declared: We were a family. We still are.

They also created a historical record. Today, genealogists, scholars, and descendants study these ads to understand family lines that were brutally disrupted. Every name in those tiny columns is a piece of America’s untold family tree.

Video:

Judith Giesberg: “Last Seen”

Preserving a Legacy of Love

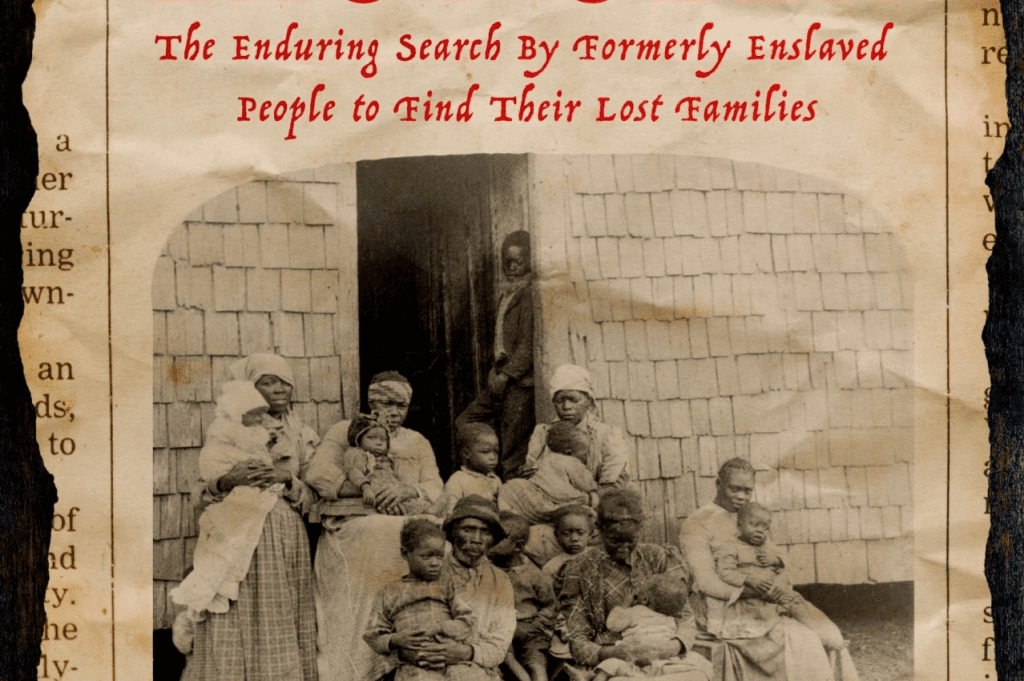

Thanks to modern digital archives, many of these ads are being rediscovered and preserved. Projects like Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery are working to digitize and analyze these fragments of personal history, giving them the attention they’ve long deserved.

For the descendants of enslaved people, these ads aren’t just words they’re threads of connection, stories that bridge past and present. They speak of an enduring hope that survived generations of trauma.

The Power of Hope in Print

The “Information Wanted” ads may have looked small on the page, but their emotional weight is immeasurable. They are proof that even in history’s darkest hour, love did not give up.

It persisted.

It reached out, again and again, across time and distance, refusing to accept erasure. And in doing so, it created a paper trail of humanity one that still speaks to us today.

So the next time you hold a newspaper, scroll through an online forum, or post a message hoping to reconnect with someone, remember: you’re part of a long tradition. A tradition that began with hope, loss, and the unshakable belief that no one is ever truly forgotten if someone is still looking.