For centuries, the ocean floor was a vast unknown an invisible, unreachable world scientists could only imagine. Most believed it was flat and featureless. But in the 1950s, one woman challenged that idea, not with dramatic expeditions or deep-sea dives, but with careful calculations, patience, and pencil lines. That woman was Marie Tharp, and her work forever changed our understanding of Earth’s geology.

At a time when women were rarely taken seriously in the scientific community, Tharp’s groundbreaking maps of the ocean floor revealed the Mid-Atlantic Ridge a continuous underwater mountain chain that provided visual proof for the once-controversial theory of plate tectonics. She was laughed at, doubted, and excluded from expeditions, but in the end, she reshaped an entire field.

Charting the Unknown from a Desk

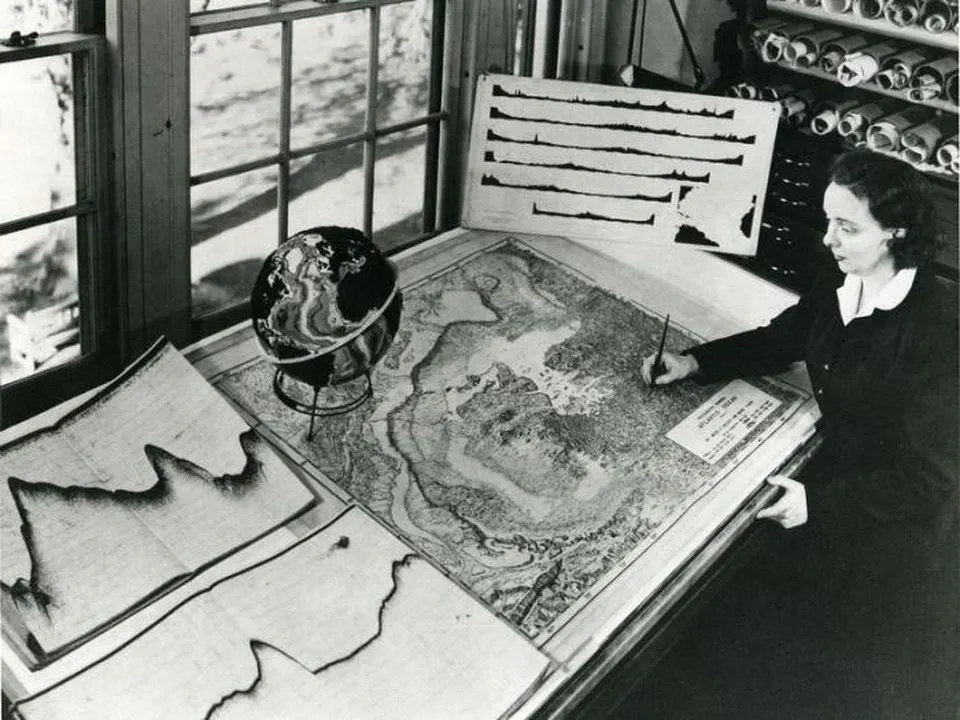

Marie Tharp began her career in the 1940s during World War II, when more women were temporarily allowed into scientific fields. With degrees in geology and mathematics, she eventually landed a job at Columbia University’s Lamont Geological Observatory, working alongside geophysicist Bruce Heezen. Her role? To take sonar data collected from ships and turn it into maps tedious work that most of her male colleagues dismissed as secretarial.

Barred from going out to sea because she was a woman, Tharp worked behind the scenes. She would pore over endless columns of soundings readings that showed the depth of the ocean floor at different points. These numbers, collected by ships using echo sounders, were as close as anyone could get to “seeing” the ocean floor at the time.

As Tharp began to connect the dots, she saw something remarkable: a deep, continuous valley running along the crest of an underwater mountain range. It was the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and the valley appeared to be a rift a place where the seafloor was pulling apart.

Video:

Marie Tharp: Uncovering the Secrets of the Ocean Floor – with Helen Czerski

A Theory the World Refused to Accept

When Tharp first presented her findings to her colleagues, including Heezen, the response was not applause. In fact, Heezen initially dismissed her rift valley theory as “girl talk.” At the time, the idea that continents moved or that the ocean floor could spread apart was still considered fringe science by many in the academic community.

But Tharp persisted. She mapped more sections. She compared her findings to data from undersea earthquakes. The evidence was overwhelming. The ocean floor wasn’t flat it was dynamic and alive, constantly reshaping itself through a process now known as seafloor spreading.

Eventually, even Heezen had to admit she was right. Their collaboration led to the creation of the first comprehensive map of the ocean floor, and their findings helped confirm the theory of plate tectonics a theory that would go on to become the foundation of modern geology.

Recognition That Came Too Late

In 1977, National Geographic published “The World Ocean Floor,” a stunning map that visualized Tharp and Heezen’s work for the public. With colorful, detailed illustrations, it allowed people around the world to see the deep rift valleys, towering ridges, and dramatic terrain that defined the ocean floor.

Video:

Marie Tharp’s Ongoing Legacy in Global Seabed Mapping Efforts

The map captivated scientists and laypeople alike. But for many years, Marie Tharp’s name was left out of the spotlight. While Heezen gained more recognition, she remained the woman behind the map a pioneer whose contributions were overlooked by a field that often excluded women from its ranks.

It wasn’t until decades later that her role was widely acknowledged. In the early 2000s, organizations like the Library of Congress and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) began honoring her legacy. Today, her name is celebrated among Earth science’s greatest thinkers.

Why Her Work Still Matters

Marie Tharp did more than just draw lines on a map. She provided a visual breakthrough that allowed scientists to see what was once invisible. Her work gave tangible form to a theory that had, until then, lacked solid visual evidence. And in doing so, she changed the way humanity understands the planet.

At a time when we continue to explore oceans and space, her story reminds us that exploration does not always require a spaceship or a submarine. Sometimes, it starts with a quiet room, a sharp mind, and an unshakable belief in what the data is telling you.

Conclusion: She Drew What Others Could Not See

Marie Tharp didn’t set out to change the world. She simply wanted to understand it. In doing so, she mapped more than just the ocean floor—she charted a path for women in science and challenged assumptions that had gone untested for far too long.

Today, every geologist who studies plate tectonics, every teacher who explains continental drift, and every student who looks at an ocean map owes a quiet debt to the woman who wasn’t allowed on the ship but drew the truth anyway.